awesome days

repentance and forgiveness unleash awesome love

“My thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways, says the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts” (Is 55:8-9).

If there is a scripture text that sums up what I might call my conversion experience, this would be it. When I was in college, I developed a true interest in matters of faith. That included, to some extent, learning about Buddhism, Zen, the Sufis (those in the mystical stream of Islam), and others. But more than anything else, the Bible started making sense to me! It began to speak to me.

In the late evening of August 3, 1985, I had an experience while reading that text from Isaiah. I felt the presence of God in an overwhelming way. It seemed like I was plunged into an ocean of love.

(I will confess I had some assistance from a substance that is now legal in our state.)

Was it like St. Augustine overhearing a child singing a rhyme, “Take up and read, take up and read,” and then reading the words in Paul’s letter to the Romans saying to abandon works of the flesh and clothe himself with Christ? Augustine felt in his heart the light of full certainty.

Was it like John Wesley in a worship service, hearing a reading (also from Romans) and feeling his heart “strangely warmed”? I don’t know. Possibly some of you can speak of similar events.

But we need not have one of those awesome experiences to accompany our initial moment of repentance. Repentance, which means “to turn around,” is often perceived as dodging a club descending from on high—or taking shelter from a divine lightning bolt. Perhaps we think of it as a darkness in which we feel worthless.

However, as Christine Vales, who does what she calls Chalkboard Teaching, says in her lesson on the month of Tishrei, that repentance “is a gift.” It isn’t a stern warning; it is a measure of grace. Aside from the loving corrective of God, we would continue to plunge into a death spiral. The call to repentance lets us know we are better than that. Despite our irrational determination to follow what is harmful and destructive, the hound of heaven nips at our heels.

Tishrei is the seventh month in the biblical calendar. However, it is the first month in the Hebrew civic calendar. It began on Friday at sundown with Rosh Hashanah (literally, “head of the year”). It is the Jewish New Year’s Day. We are now in the year 5784.

Fun fact: year 1 on the calendar is the day of Creation, at least according to the 12th century Jewish philosopher Maimonides. He actually was quite a genius, even while dealing with 12th century science.

There are ten days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. They are called the “Days of Awe.” I really love that name. The days of awe.

I’m reminded of a movie that goes on the list of my favorites, at least in the first decade of the 2000s. It’s The Fountain, starring Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz. I won’t pretend to do it justice, other than to say it involves three intertwining storylines—the past in the 1500s when the Spanish invaded Mayan territory, the present when a doctor desperately fights to save his dying wife, and the distant future when a voyager eats of the tree of life from Eden and has a cosmic experience.

The movie’s thematic quote: “Death is the road to awe.”

At the risk of too easily manufacturing a segue, the days of the passion of Christ prove that indeed death is the road to awe. His conquering of death is nothing else but the essence of awe.

So let’s return to Yom Kippur, also known as the Day of Covering—the covering of sins, the forgiving of them.

In Leviticus 16, we see a description of Yom Kippur, which was set aside as a communal time of repentance. The High Priest would enter the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctum of the temple, and offer a sacrifice. It was the only day of the year he was permitted to do this. He would sacrifice a goat to atone for the peoples’ sins.

Afterwards, we see in verses 20 to 22, a reference to Aaron, the brother of Moses, and the first of the priestly line.

“When he has finished atoning for the holy place and the tent of meeting and the altar, he shall present the live goat. Then Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat and confess over it all the iniquities of the Israelites, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task.”

This person would guide the animal into the wasteland and wait until it could no longer be seen.

Verse 22 says, “The goat [that is, the scapegoat] shall bear on itself all their iniquities to a barren region, and the goat shall be set free in the wilderness.” According to tradition, the wilderness was the dwelling place of Azazel, a fallen angel who personified uncleanness. Azazel embodied ritual impurity. It was often said Azazel was the devil’s right-hand man. I don’t know, would that look good on a résumé?

On a personal note: maybe you have noticed this year I have developed an interest in the biblical months. It might be asked, “Why as Christians should we care about the feasts in the Bible?”

Christine Vales gives her answer. She says of the feasts and why she observes them, “They draw my heart to [Jesus], closer and closer every year, as I enter in… We don’t have to celebrate the feasts. We get to celebrate the feasts” (at 22:30). She comments, “Tishrei is full of feasts and fasts and shofar blasts” (at 7:08).

I won’t promise I will be sounding the shofar, which is especially prominent during this month, representing as it does a call to repentance. But I can resonate with the significance.

https://jwa.org/media/girl-blowing-shofar

Nonetheless, I would be remiss to not acknowledge the words in the epistle to the Hebrews that it “is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (10:4). Furthermore, as chapter 10 says, the priests stand “day after day at [their] service, offering again and again the same sacrifices that can never take away sins” (v. 11). However, “by a single offering [Christ] has perfected for all time those who are sanctified” (v. 14).

So transitioning from Yom Kippur to the fulfillment in Jesus Christ, let’s see what the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew 6 has to say about forgiveness.

Before we go any further, there is the usual question of which to use in the prayer: “debts” or “trespasses.” When I preside before an ecumenical group (which often happens at funerals) as opposed to one primarily Presbyterian, I will say “debts” and then pause, waiting for those trespassers to catch up. Though sometimes I will relent and say “Forgive us our trespasses…”

The question hinges on verse 12. Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors. The Greek word, οφειλημα (opheilēma), first of all has the meaning of money or some other legal liability. However, there is a secondary meaning which has a spiritual sense. So we’re the ones who have it right!

In this translation (the New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition), it reads, “And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” The idea is forgiving is something that has already been done and is expected to continue. This isn’t just some fine grammatical detail; it carries theological weight.

“Trespasses” appears in verses 14 and 15. It is a different Greek word, παραπτωμα (paraptōma). It has the meaning of “falling beside something,” or more specifically in this case, “a lapse or deviation from truth and uprightness”—a sin or misdeed.

Forgiveness and repentance are bound up with each other. And so often they do not come easily. An extreme example would be forgiveness when a family member has been murdered. There was a story reported in Today.com about a mother who suffered that horrific tragedy, that horrendous crime.

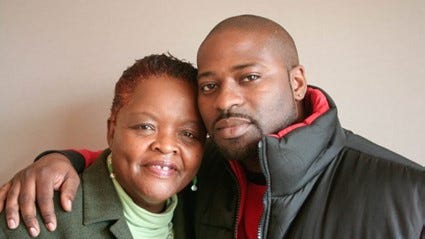

“Mary Johnson, 61, knows something about forgiveness: she has hugged the man who murdered her only son.

“While that profound moment was only possible after years of turmoil and prayer, Johnson tried to start down the path of forgiveness after tragedy struck: At the sentencing for Ohsea Israel, the teenager who shot her 20-year-old son Laramiun Byrd to death at a party in 1993, Johnson told him she forgave him.”

I imagine we all have heard other cases of this nature.

The story continues, saying “her faith guided her on an unpredictable journey, and eventually led her to embrace Israel in a prison conference room following a two-hour conversation.

“Afterward, Johnson became hysterical, doubled over in shock, and kept repeating the phrase, ‘I just hugged the man that murdered my son.’

“It was then, Johnson recalls, that she was set free. ‘I felt something leave me,’ she said. ‘Instantly I knew all the hatred, bitterness and animosity—I knew it was gone.’”

Even more remarkably, “Johnson calls Israel her ‘spiritual son’ and he refers to her as a ‘second mom.’”

“Johnson said her forgiveness of Israel in no way condones what he did 20 years ago, but that she did it to free herself of suffering. ‘All that stuff had to leave me,’ she said. ‘And the day I went to prison [to visit him], I was delivered.’”

Being able to forgive is a powerful remedy. It’s a powerful remedy in all directions. Notice I said, “being able.” As we heard earlier, repentance itself is a gift. In the same way, so is the grace of forgiveness. It’s difficult to conjure it up at will, especially in cases like Mary Johnson’s.

In many ways, forgiveness is a spiritual discipline. Believe it or not, we have opportunities to practice it all the time. Consider this. When someone cuts you off in traffic, how often is forgiving the other driver the first thought that pops into your mind?

Back to more serious aspects we read, “For if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you, but if you do not forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.” That sounds suspiciously like a quid pro quo. I do something for you; you do something for me—making a deal. It sounds like God’s forgiveness is conditional.

Here’s another way of looking at it. “And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” As I said about forgiveness being a spiritual discipline, it can become part of our very nature. It is who we are. We receive what we put out. If we emit positive, holy energy, that’s what comes back. However, if we emit negative, unholy energy, that also is what comes back.

Taking a step further, is there something we need to forgive ourselves for? Maybe there’s something we’ve been carrying around, and there’s really no need to do so. Maybe we need to repent, to do that turnaround, and the burden will be lifted. After all, there is one who said, “Come to me, all you who are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest” (Mt 11:28).

Here’s what might be an unexpected question. Do you believe God owes you an apology? Trust me, you wouldn’t be the first to feel that way. Read the Bible. There are numerous psalms in which that very expectation is uttered. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning?” (22:1). Even Moses was angry with God. “Why have you treated your servant so badly? Why have I not found favor in your sight, that you lay the burden of all this people on me?” (Nu 11:11).

“I demand an answer!” There many such cases in the scriptures.

Friends, we are in the midst of those days of awe, those awesome days. Whether we’re literally talking about these days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, or some awesome days in a more general sense, we can experience them. We can open ourselves, we can welcome, the repentance and forgiveness that has the power to change us and to heal us—mind and heart and soul, and even physically.

The Spirit of regeneration and renewal is present among us, right here, right now. We can pray for the grace to allow the Spirit to do what liberates, to do what sets us free from all of the crap we lug around.

Jesus the Messiah has a desperate yearning to see us turned around and transformed in his full glory.