November 1 was All Saints’ Day. When the first Sunday of November doesn’t fall on the first, we celebrate it as All Saints’ Sunday. In Christian liturgy, we recall those in the faith who have gone before us. Here are some: the apostle Paul, Hildegard of Bingen, Harriet Tubman, Desmond Tutu, and Jim Moore (my father).

Maybe we all could add folks near and dear, such as “a,” “b,” and “c.”

Maybe we all could add folks not so near and dear, such as “x,” “y,” and “z.”

There are several scriptures associated with All Saints’ Day. Among them: “since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight and the sin that clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us” (Hebrews 12:1).

photo by Rodion Kutsaiev on Unsplash

Chapter 11 speaks of Hebrew heroes of faith.

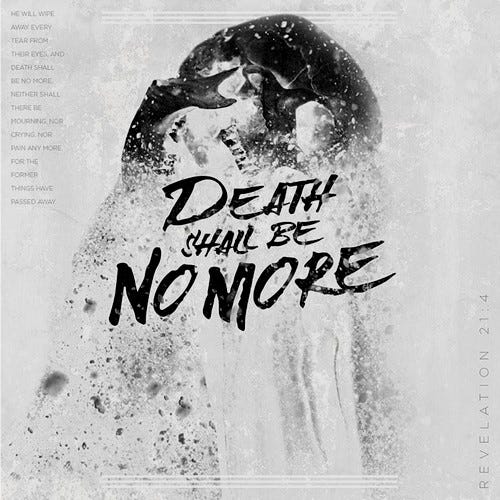

Revelation 21:3-4 promises “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them and be their God; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away.”

The cloud of witnesses, those heroes of the faith, the first things having passed away—all of these include considerations of time. Woven into time is memory.

What happens when we do not remember well? How does that affect our relationship with others? What if we have been trained, even indoctrinated, to disregard the accomplishments and humanity of others?

It’s actually more than a question of others, it is “certain others.” Indeed, those others could be vile, sub-human critters. At least, we might picture them as such. Indeed, those critters would not be worthy of having getting folks together and planning them a birthday party!

What does this say about “saints everywhere”?

At the time I’m writing this column, the fighting in Gaza has progressed—or maybe I should say regressed—quite a bit. As we all know, the turmoil in this region goes back for decades, even centuries.

Still, the events on the morning of October 7 were not of the usual military nature. (Not like that in itself is anything less than horrendous.) Nonetheless, those were not the actions of soldiers but of savages. Ghastly deeds were done. It should be noted this wasn’t a reaction in the heat of the moment. The massacre of civilians, murder of concert attenders, mass rape, the kidnapping of scores of hostages—all of this was carefully planned. But please understand, I in no way agree with the Netanyahu government’s vast overreaction in response.

Admittedly, I compose these words from the safety of my home thousands of miles away. And yet, it is in my home country in which the bigotry and antisemitism always present has risen to the surface.

Okay! How about we get back to “saints everywhere”?

So much depends on perspective. If one is looking for a reason to find fault, then such a reason can be found. If one is looking for a reason to find fault with a vengeance, then such a reason can be found—with a vengeance!

On the flip side, if one is looking for saints, then saints shall be found. Saints need not be the “official” ones recognized by many church traditions: St. Benedict, St. Joan of Arc, St. John Paul II and so on. There are saints as described in the New Testament, the ones who are believers.

In the New Testament, the saints are not simply the dearly departed. Rather, they are living, breathing, and moving around. They are being transformed by God.

In that transformation, there is no room for fault-finding and certainly no fault-finding with a vengeance. Having said that, are saints perfect? Absolutely not. In fact, saints and sinners inhabit the same bodies. Something else about saints: they are known and unknown.

Saints live lives of repentance, which means “to turn around.” Saints encourage others to live lives of repentance. Those others are you and me and those who commit ghastly deeds.

That repentance and transformation is nothing less than saintly.

“Death will be no more / mourning and crying and pain will be no more / for the first things have passed away”